A War Diet Poem

"We Were Not Vegetarian from Choice"

Tom Earley, a Welsh poet revisits his childhood meals during the war-time in his poem, "For What We have received". Published in 1992, this poem reflects back on past memories and the feelings that were evoked through his experience with food. Earley's poem explores issues and concepts also present in the recipes I have analysed within previous posts including: the overuse of vegetables, the lack of meat and the cultivation of produce.

The consumption of food in the poem seems to be reliant on the cultivation of produce. He mentions in the first few lines: 'allotment salad seemed free' (3). Although, there is essentially no price for cultivating your own produce, Earley is aware of the "price" of the hardwork that comes with the process. The picking of fruits is also described in the second stanza: 'whichever fruit our indigo fingers had picked that golden day’ (13-14). He presents to the reader the physical process of harvesting produce for meals, the 'indigo fingers' representative of the hard work that goes into cultivating crops.

|

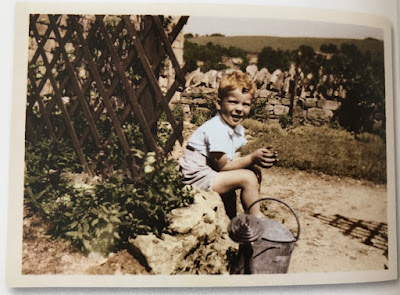

| Fig 1: Like the Young boy in the photograph, Earley and other children were expected to take part in the cultivating of produce. p.10 |

The middle of the poem presents to the reader the anxiety of portions during the war-time. He describes how his mother ‘served geometrically neat, which exactly equal slices, making fair shares for all’ (18-20). He puts a lot of emphasis on amounts and portions, as I have mentioned before rations meant smaller portions and less options!

The poem begins with the lines: ‘we were not vegetarian from choice but from necessity’ (1-2). Earley and his family are presented with lack of choice when it comes to food, the lack of meat transforming them into vegetarians, unintentionally. Throughout the poem there is tension between the meat and the vegetables. The vegetables are often described as meaty, living "things". He starts off by describing the lettuces as 'fragile' and young' (4-5), personifying them and transforming them into infantile "beings". Earley goes on to describe the beetroot with 'deep purple flesh', creating this meaty imagery. The interchanging qualities that he gives the meat and vegetables at the beginning, emphasises his craving for meat.

He mentions waiting all week 'for the Sunday joint’ on line 25 and follows up by describing the the emotions he felt, knowing he was about to feast on some meat: ‘the small sweet mountain mutton’ (29). The alliteration of 'small' and 'sweet' and 'mountain mutton' only emphasises the excitement he has for this meal. Earley goes into great detail when describing the meat: ‘shoulder of lamb with its crisp’ (31), ‘brown crust of fat’ (32), ‘breast of lamb’ (33). The different parts of the meat are mentioned separately, including the fat! For Earley and his family all parts of the meat become delicious and highly appreciated, after being deprived of meat for so long! He does also describe the vegetables in great detail in conjunction to the lamb: ‘green parsley stuffing’ (34), ‘spring greens, and yellow waxy new potatoes’ (36-37). The description of the potatoes as 'waxy' suggests their fresh quality and unreal perfection, he even follows up with the line: ‘from our own garden’ emphasising how fresh the vegetables are.

The ending of the description is brought to an abrupt end with a full stop. The last two lines read: ‘But the meat was the thing: we were not vegetarian from choice’ (39-40). Earley finishes off the poem with the same lines that he starts with, reminding the reader that despite the freshness and the deliciousness of the vegetables, the meat is far superior and the real object of his desires.

Work cited:

Earley, Tom. All the Trees. Llandysul: Gomer Press, 1992, p.66. Print.

Images cited:

Fig 1: Way, Twigs. Allotment & Garden Guide: A Monthly Guide to Better Wartime Gardening. Kent: Sabrestorm Publishing, 2009. Print.

Images cited:

Fig 1: Way, Twigs. Allotment & Garden Guide: A Monthly Guide to Better Wartime Gardening. Kent: Sabrestorm Publishing, 2009. Print.

Comments

Post a Comment